Flood poses risk to property and productivity on every continent, and most developed countries have flood insurance available to mitigate that risk. However, everywhere you go, the flood insurance market is different.

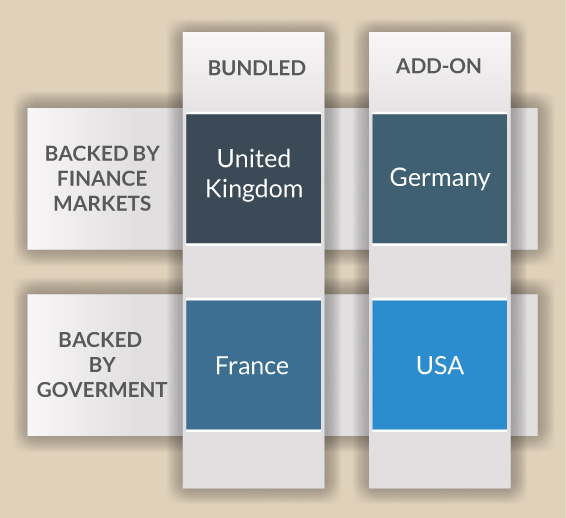

There are four principle types of flood insurance models around the world, differentiated by who backs the insurance (government or private markets), and whether it’s bundled or separate from other property insurance coverage (e.g., flood and fire insurance are frequently bundled together).

Each style has its own pros and cons, and each exists in its region for a variety of reasons. Here is a quick look at the four types.

Bundled flood insurance, backed by private markets.

In this market model, flood insurance is basically included with your insurance policy — whether you want it or not. Insurers add the flood coverage onto all policies, thus maximizing the risk pool (which keeps costs low), diversifying risk across all the perils together (which also removes the attribution problem [“What caused the damage?”]), and ensuring solid penetration into the market. This is the U.K. model, and is also used in countries like Hungary and China. It is a very effective system for the success of flood insurance, offering wide coverage to property owners at affordable prices while ensuring the insurance industry remains not just solvent, but profitable.

Bundled flood insurance, backed by government.

This is the socialized version of the U.K. model, where the government administers mandatory coverage for flood and other perils on all property insurance policies. The French and Spanish systems are the most predominant examples of this system. The insurance policies are still written and sold by private insurance companies, but in this model, the state maintains a pool of capital by collecting a portion of all premium collected to back the policies in the case of claims. This system is a secure market for insurers to operate, and is thus attractive to the industry. Another characteristic of this system is that as development of land continues, and catastrophes increase in frequency, the state is incented to ensure the risk of natural catastrophe is minimized, by defending rivers or limiting development in flood zones.

Optional flood insurance, backed by private markets.

Known as the German model, Germany, Austria, and South Africa carry this system, in which insurers depend upon policy holders deciding to insure their property for flood. This is the most laissez-faire of the systems, but as with any insurance market where coverage is optional, the problem arises from the market being concentrated on the high-risk segment only. Prices are hard to keep low if claims are likely on the majority of policies sold, which limits penetration and doesn’t offer wide coverage for the society. A possible reason for this is the belief in these countries that flooding and other potential catastrophes should be taken into account by property owners when they build/purchase their buildings.

Optional flood insurance, backed by government.

This is the U.S. model, known as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), implemented by FEMA. As with the German model above, this system struggles under the concentration of policies in high-risk areas. Unlike the German model, the NFIP is subject to political pressure to maintain prices lower than actuarial prices, leading to enormous shortfalls of capital ($17.5B over the 40 year life of the NFIP through 2008). A further weakness of all optional systems is that they are over-reliant on the quality of flood maps for risk designation. Typically in the U.S., half of the flood losses occur outside designated risk areas, of which 1% was insured for flood, meaning enormous amounts of property subject to flood risk are uninsured.

Countries with nascent flood insurance.

There are a handful of developed countries that do not yet have fully implemented flood insurance markets. Developing nations begin to have flood insurance markets as their property and productivity become valuable enough to insure. Other developed countries, such as Canada, don’t have flood insurance due to assorted market conditions or lack of demand. In 2010, the city of Winnipeg was the site of a pilot project to try introducing flood insurance to Canada, but it was canceled as only 30 policies were sold. It remains to be seen what system these countries with emerging flood insurance markets will eventually implement.

Each country has its own system of flood risk that is based on local conditions and history. Some are demonstrably more effective than others, but in every case it’s a combination of factors that determines how flood insurance is bought and sold. The only constant among all systems is that they are changing and evolving to always better fit the market and the natural catastrophes as they happen.