Summer is here, and in the Pacific Northwest and Western Canada, it really feels like it. Record highs are being set all over the region, the Calgary Zoo is closed so the animals can be cooled, and the wildfires are burning.

The most newsworthy wildfire so far is the Sleepy Hollow wildfire in Wenatchee, WA. It's burning homes and industrial buildings, and as of today is only 10% contained. It will get bigger before it gets smaller.

Northern Alberta and Saskatchewan are experiencing many wildfires, with several small communities being evacuated. Again, no respite is on the horizon as the weather is forecast to continue as very warm and dry. British Columbia has its fires, too, with Vancouver air quality suffering with the smoke — residents are being asked to avoid strenuous activities in the afternoon, which defeats the purpose of living in Vancouver for many of them.

Wildfire continues to be a predominant problem for government agencies, especially those responsible for emergency response and the management of natural resources. Fire crews are flying into the hotspots from all over the continent now to lend a hand, and FEMA is active in Chelan County, WA.

Yet for the property insurance industry, wildfire continues to be considered a fringe peril, or even an “unmodeled” peril in some circles. Compared to other natural perils, the losses from wildfire are definitely small for insurers — but it is anything but “unmodeled”.

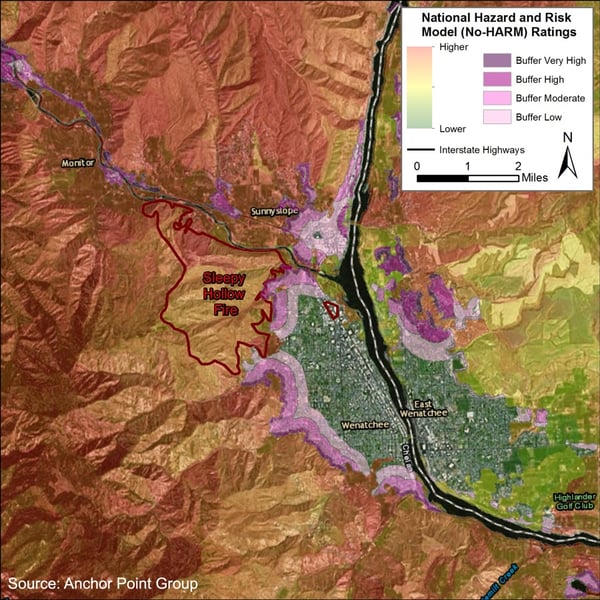

There are wildfire models available now that are definitely robust enough to underwrite property with some confidence, including AnchorPoint’s NOHARM for the USA. Below is a graphic of the current extents of the Sleepy Hollow Fire, overlaid on NOHARM. Note how the model captures the edge of the fire with a change in burn likelihood where the natural fuel ends and the structures begin. This is the expected behavior of a wildfire in the WUI (Wildland Urban Interface), and the model has nailed it. The pink and purple areas east of the fire are the ember zones, where there is a risk of fire ignition due to wind-borne embers. For Canada, the data exists to create underwriting-caliber models, as well.

The key to any model being usable for underwriting property insurance is that it needs to take a long view at the chance of a fire burning in a specific location. Most publicly available wildfire models are built to describe what kind of fire would burn in a location if it ignites. These models are used primarily for timber inventory management and emergency preparations.

It is inevitable that wildfire will become a more prominent peril for property insurers because it causes significant losses AND is well modeled. Well-modeled perils are few, and insurers looking to expand their share of a property market in North America or Australia should really consider expanding their wildfire products. Insurance has always thrived where there is danger – look no further than Wenatchee right now to see where the opportunity lies.