Today we decided to unlock the Intermap blog vault to revisit a a past post written by a former employee, Ryan Hamilton. His thoughts on pipeline safety and the relationship to terrain data were written a little more than a year ago, but are more relevant than ever as we roll out our new product targeted to this very industry — InsitePro for Pipelines™.

Ivan Maddox

Recent Posts

Topics: Pipeline Operations, Terrain Data

Peril, risk, and hazard are three words used frequently in my business. And according to the Oxford English Dictionary, they have very similar definitions:

- Peril: Serious and immediate danger.

- Risk: Situation involving exposure to danger.

- Hazard: Danger or risk.

You could get away with interchanging these words in day-to-day conversation. But in insurance and financial circles, they each have a distinct meaning and it’s important to understand their differences.

Topics: Natural Hazard Risk, Risk Management

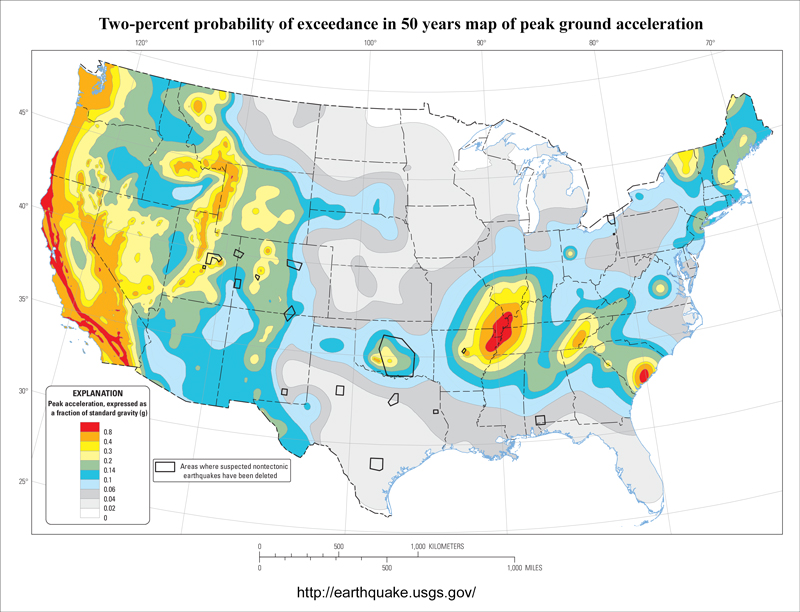

Property insurers rely on many types of tools for risk analysis, but none quite so complex as the cat model. Short for catastrophe, cat modeling uses computer-assisted calculations to estimate the losses that could be sustained due to a catastrophic natural event. Perils analyzed include flood, hurricane (wind damage and storm surge), earthquake, tornado, hail, wildfire and winter storm. The principle function of cat models is to help insurers prove their financial solvency.

Topics: Natural Hazard Risk, Natural Catastrophe, Other Risk Models

Flood poses risk to property and productivity on every continent, and most developed countries have flood insurance available to mitigate that risk. However, everywhere you go, the flood insurance market is different.

Topics: Flood Insurance, Insurance Underwriting, Flood Modeling

Why FEMA Flood Maps Don't Tell the Whole Risk Story

Posted by Ivan Maddox on Dec 3, 2014 10:09:00 AM

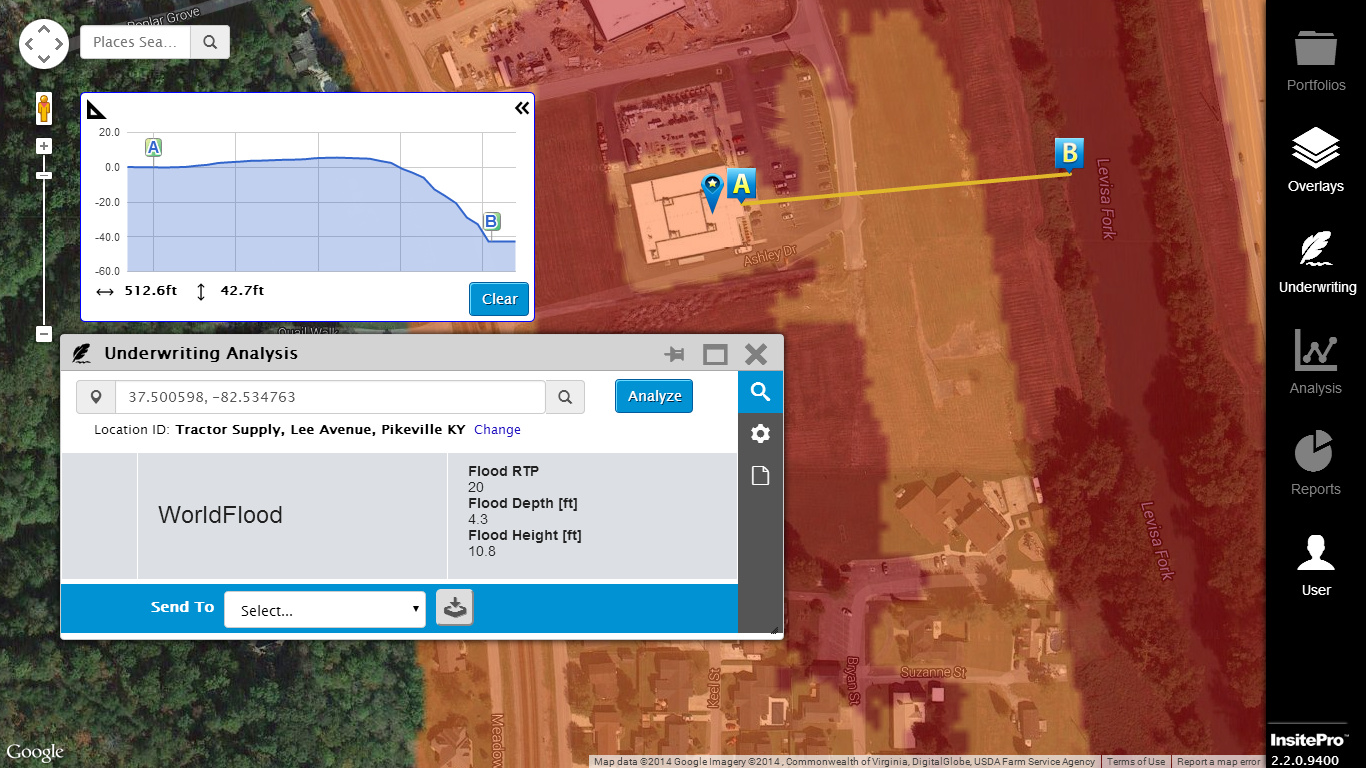

When it comes to flood risk, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)'s Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) are the authority — and rightly so. They have decades of engineering intelligence built into them and are refined regularly. In the end, though, they are based on flood models, and as statistician George Box famously wrote, "essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful."

A recently published report that investigated how well the FIRMs predicted flooding from Superstorm Sandy in 2012 illustrates that while they performed well in some areas, there is also room for improvement. That's because there is no flood model, or model of any natural catastrophe, that will be 100% accurate. In fact, predicting 100% of a flood event is usually a sign of a weak flood model: Imagine a model where everything within 100 miles of water is labeled as High Risk. Flood models display their quality in the zone between, “You don’t need a model to know that’s a flood risk” and “that place will never flood”. In statistical terms, the sweet spot is around 75% or 80% of flooding predicted. This is about where FEMA's FIRMs were on Sandy, but there is more to understanding flood risk than statistics.

Topics: InsitePro, Flood Modeling, Flood Risk